Sharp increase in government debt threatens to derail global economy, meaning investors must be discerning of countries they focus on

Publishing date:

Oct 25, 2022 • 4 days ago • 5 minute read • 7 Comments

A group of tourists walk past a temple in Thailand. The country is among countries investors may want to focus on. Photo by Taylor Weidman/Getty Images By David Rosenberg and Krishen Rangasamy

Advertisement 2 This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

After enjoying decades of low borrowing costs, courtesy of the global savings glut, governments are now under pressure across the globe. Some have been entirely shut out of financial markets (Russia, Pakistan and Sri Lanka come to mind), while others are facing the highest interest rates in decades.

FP Investor By clicking on the sign up button you consent to receive the above newsletter from Postmedia Network Inc. You may unsubscribe any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link at the bottom of our emails. Postmedia Network Inc. | 365 Bloor Street East, Toronto, Ontario, M4W 3L4 | 416-383-2300

The combination of elevated debt levels, rising interest rates and weak economic growth increases the odds of sovereign defaults, which, in turn, have potential to spill over to an already-weakened private sector via ties between government and banks.

As such, investors would do well to be discerning, focusing on economies that have manageable public debt, good current account positions, healthy foreign currency reserves and a relatively weak sovereign-bank nexus. Countries such as Thailand, Taiwan and Malaysia screen well on those measures.

Advertisement 3 This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

COVID-19 debt legacy One of the legacies of the COVID-19 pandemic, namely the sharp increase in government debt, is now threatening to derail the global economy. Advanced economies’ gross debt climbed to more than 112 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2022 from roughly 104 per cent of GDP in 2019, according to the International Monetary Fund’s latest World Economic Outlook. Emerging markets had an even faster increase, up 10.5 percentage points over that period to reach 64.5 per cent of GDP in 2022.

Among advanced economies, Japan and New Zealand have led the charge in terms of debt accumulation (amid the fight against COVID-19), both having an increase of more than 20 percentage points in their gross debt-to-GDP ratios. Others, including the United States, Canada and major eurozone economies, have also had double-digit increases over the past three years.

This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

Article content In emerging markets, Sri Lanka sticks out with a near-48 percentage point increase to 130 per cent of GDP (no wonder that country is now in default), while Bolivia, the Philippines and Thailand all had increases of more than 20 percentage points. China, Tunisia, Malaysia, Korea, South Africa and Indonesia also had double-digit increases over that period.

Inflation, rising bond yields and debt-servicing costs This debt accumulation was, of course, made possible by a low interest rate environment, courtesy of a global savings glut and loose monetary policy by central banks, particularly in advanced economies. But now it’s time to pay the piper.

This year’s inflation shock has prompted a U-turn in central-bank policy, pushing up interest rates across the yield curve in most countries, leading to higher borrowing costs for governments. For instance, 10-year government bond yields have shot up since the start of the year by about 3.5 percentage points (ppts) in Greece, Italy and the United Kingdom (although the latter two are partly due to the uncertain political climate). In emerging markets, 10-year yields have shot up as well: Mexico (2.3 ppts), Korea (2.1 ppts), South Africa (1.5 ppts) and Brazil (1.2 ppts).

This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

Article content The surge in bond yields, coupled with earlier debt accumulation, translates to significant increases in debt-servicing costs for many countries. The eurozone’s GIPS (Greece, Ireland, Portugal and Spain) economies are the worst affected, given the relatively large size of their government debt and surge in bond yields, although the U.S. and the U.K are not far behind.

The debt-service shock is less acute in emerging markets given their relatively lower government debt levels, although still significant, at around one per cent of GDP in places such as Korea, Brazil, South Africa and India.

Some complicating factors This is not to say that emerging markets are in the clear. The strong U.S. dollar represents a major risk to that group, given that nearly 16 per cent of public debt is denominated in foreign currencies (compared to just three per cent in advanced economies). Any trouble with public finances has the potential to spill over to the private sector given the deepening ties between the sovereign and banking sectors.

This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

Article content Note that banks in emerging markets now hold more than 17 per cent of their government’s sovereign debt, up from roughly 14 per cent before the pandemic. This stronger sovereign-bank nexus, as we saw during the eurozone’s sovereign debt crisis, can threaten the stability of the economy and financial system.

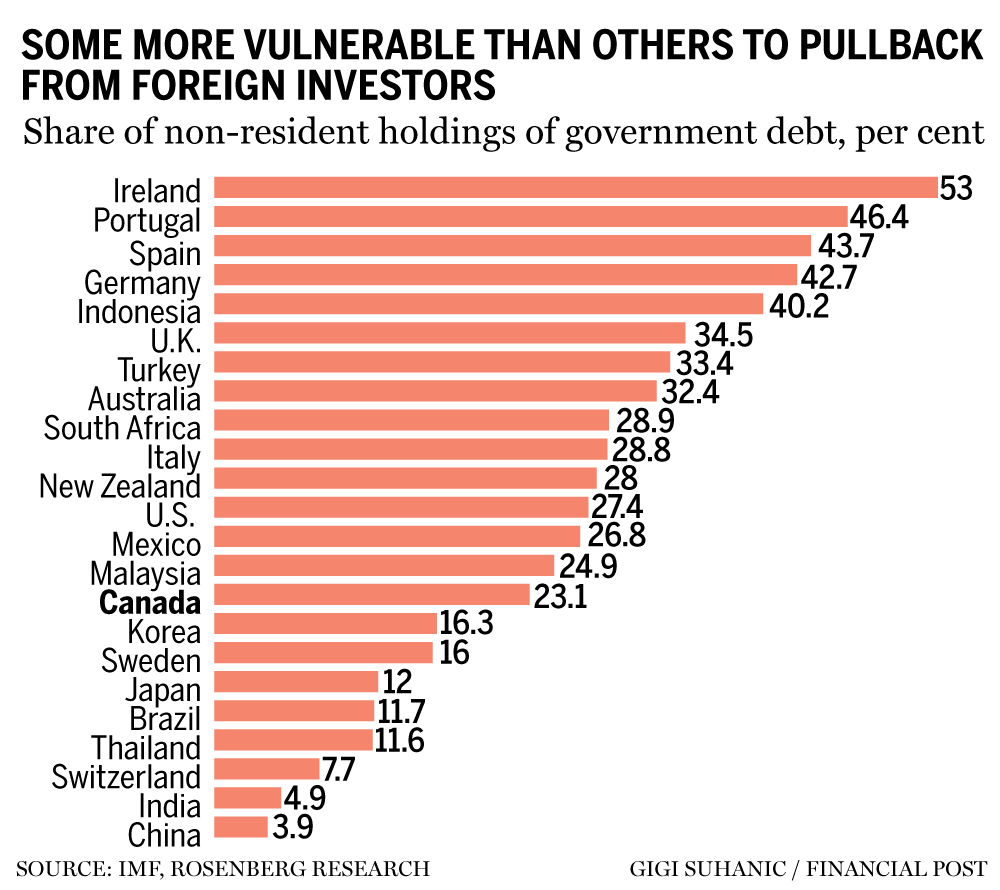

Another complication for emerging markets is capital flight. Countries with high shares of non-resident holdings of government debt are more vulnerable than others. Here, we’re thinking of places such as Indonesia (where foreigners hold as much as 40 per cent of government debt) and Turkey (where foreigners hold about a third).

It’s true that several advanced economies have even higher shares of foreign ownership (for example, Ireland, Portugal, Spain and Germany). But they are also better able to cope with capital flight than emerging markets thanks, in part, to their ease of access to financial markets, and because they are backed by powerful central banks that can help cushion the blow of rising bond yields — the European Central Bank’s new “Transmission Protection Instrument” and the Bank of England’s recent interventions are examples.

This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

Article content David Rosenberg: Canada’s message to the rest of the world: Bring us your workers David Rosenberg: Goodbye TINA, hello safety and income at a reasonable price David Rosenberg: Equities are generally not pricing in a recession yet, but one asset class is David Rosenberg: Make no mistake, the Fed is guiding us into a credit crunch The combination of high government debt and rising borrowing costs suggests that fiscal policy, unlike in the past two global recessions, is not in a position to cushion the blow of the upcoming economic downturn. No wonder the IMF is now expecting world real GDP growth of just 2.7 per cent in 2023, the worst since the 2020 COVID-19 recession.

But things could be even worse than what the IMF is currently expecting if the U.S. dollar and bond yields continue their uptrend, capital flight gathers steam and the deep ties between the sovereign and banking sectors prompt spillovers from government to the private sector.

As such, investors would do well to be discerning, and focus on countries such as Thailand, Taiwan, and Malaysia that have manageable public debt levels, good current account positions, healthy foreign currency reserves, and a relatively weak sovereign-bank nexus.

David Rosenberg is founder of independent research firm Rosenberg Research & Associates Inc. Krishen Rangasamy is a senior economist there. You can sign up for a free, one-month trial on Rosenberg’s website.