Investors have passed miners by amid growing confidence in ability of central banks to stave off systemic crises

Gold miners appear to have lost their safe-haven status even as gold prices perform as expected in a crisis. Photo by Andreas Gebert/Bloomberg Gold miners should be some of the happiest people on Bay Street.

Advertisement This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

Central banks have spent the past couple of years pumping trillions of dollars into the global economy, precisely the kind of thing that makes gold bugs crazy and typically drives up demand for a metal that humans have valued for centuries.

Inflation has surged to its fastest pace in more than three decades, and geopolitical rivalries haven’t been this intense since the Cold War. If investors ever needed a safe haven, it’s now.

Gold miners have long pitched themselves as something akin to portfolio insurance, an asset class as solid as the metal they dig out of the ground, which is supposed to hold its value at normal times, and rise when a panic-inducing crisis occurs.

But this crisis has largely passed miners by.

Advertisement This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

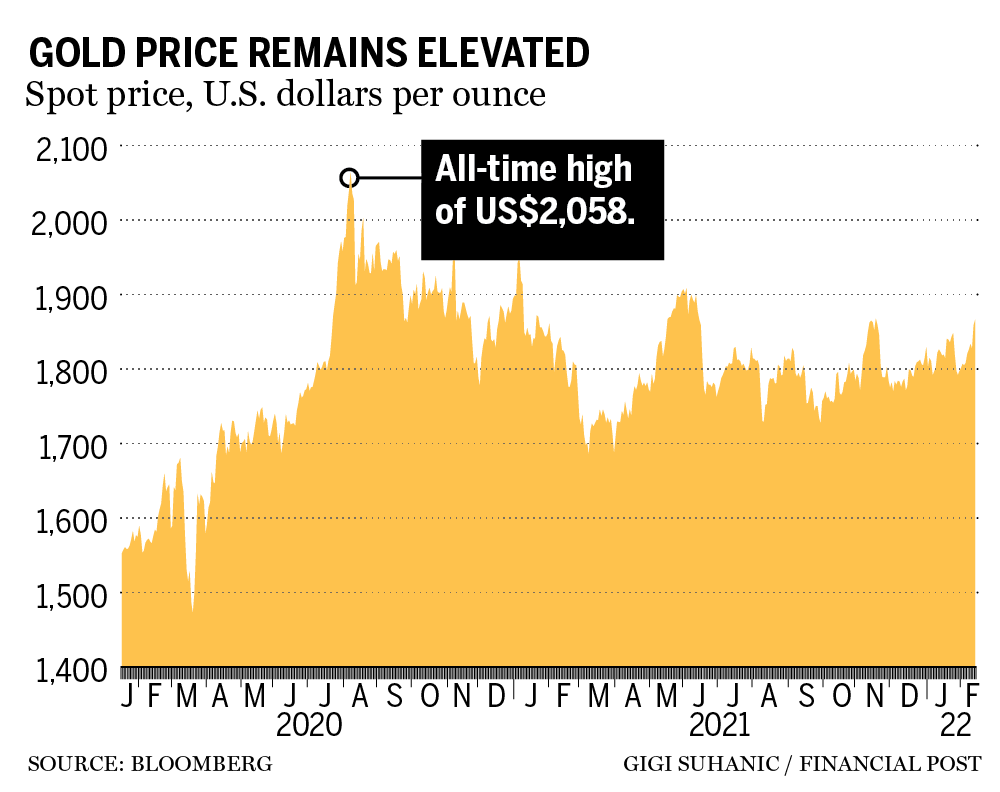

Gold itself has performed as advertised: the commodity touched an all-time high of US$2,058 per ounce in late 2020 and it remains elevated at around US$1,862 per ounce, roughly 12 per cent away from its immediate pre-pandemic high.

As a result, gold mining companies are reporting higher profits, but those gains aren’t reflected in stock prices. Their shares have underperformed both gold and the broader stock market, raising questions about whether something about their industry has fundamentally changed in recent years.

If the worst global pandemic in more than a century isn’t enough to stoke interest in gold miners, what’s going to happen when things settle down? Why invest in their sector at all if it underperforms during a crisis?

Advertisement This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

“It’s kind of like the Rodney Dangerfield phase, where everybody’s saying, ‘I get no respect’,” said Jason Neal, a veteran mining investment banker and board member of G Mining Ventures Corp., a junior exploration company.

A range of factors could explain why gold stocks have underperformed. One would be the popularity of technology stocks such as Alphabet Inc. and Microsoft Corp., which have soared over the past two years, suggesting investor appetite for risk has superseded a desire for the insurance that gold mining companies could theoretically provide.

If the worst global pandemic in more than a century isn’t enough to stoke interest in gold miners, what’s going to happen when things settle down?

Many gold mining executives, however, have fixated on something else. They wonder if investors have become more confident in the ability of central banks to stave off systemic crises such as the global credit crunch that followed the collapse of Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. in 2008.

Advertisement This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

Back then, the United States Federal Reserve was forced to experiment with creating money to keep financial markets liquid, an aggressive form of monetary policy known as quantitative easing (QE).

If the goal was avoiding a depression, the experiment worked, equipping central banks with a new playbook. QE was deployed without hesitation to fight the recession caused by the lockdowns to slow the spread of COVID-19.

“The whole reason for holding a gold equity is largely gone because of governments covering every crisis,” said Andrew Kaip, a former top gold analyst at BMO Financial Group who is now chief executive of Karus Gold Corp., a Vancouver-based exploration company.

”Go back to the (2008-09) financial crisis: we didn’t know if quantitative easing was going to work, the global outlook was very uncertain,” he added. “This time around, everybody knows what the outcome is … we know they’re going to save our asses.”

Advertisement This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

Yet Barrick Gold Corp.’s stock on Monday was trading at around $26, about where it stood in August 2019, months before anyone had heard of COVID-19. Agnico Eagle Mines Ltd. was trading near $63, but it was at $83.24 in August 2019.

The whole reason for holding a gold equity is largely gone because of governments covering every crisis

Andrew Kaip

The effects of stimulus don’t seem to have provided the same kick for either gold or gold mining companies as they did a decade ago.

Between 2008 and 2011, the price of gold rose 174 per cent to about US$1,896 per ounce from about US$692 per ounce. Investors were apparently more spooked then by the death of a handful of Wall Street investment banks than by a killer virus now. The price climbed about 39.5 per cent between March and August 2020, and is currently only 24 per cent higher than in March 2020.

Advertisement This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

Yet the volume of fiscal and monetary stimulus has been far greater during this crisis. Last June, McKinsey & Co., the global consulting firm, estimated that governments around the world had already injected $10 trillion in stimulus into the global economy, triple what was used during the 2008-09 crisis.

A contractor works at an Agnico Eagle Mine in Quebec. Photo by Valerian Mazataud/Bloomberg The amount of stimulus has continued to grow since then, as U.S. President Biden tries to push through Infrastructure bills and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau maintains many support programs.

Meanwhile, The VanEck Vectors Gold Miners ETF (GDX:NYSE), a basket of gold mining and gold streaming stocks, is essentially flat, with its high point in February 2020. It’s been propped up by gold streaming and royalty companies, which many executives say have created an increasingly attractive investment alternative to mining companies during the past 15 years.

Advertisement This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

Such companies help finance projects by providing cash to gold miners upfront in exchange for a portion of the gold produced, or a cut of the profits from a mine. As a result, they can hold stakes in many more mines than a gold mining company, which creates insulation against the social and environmental challenges of actually operating a mine.

Exchange-traded funds backed by physical bullion offer yet another way for investors to gain exposure to gold without ESG concerns. Photo by David Gray/Bloomberg Canada’s two largest precious metal streaming companies by market cap, Franco-Nevada Corp., at $33 billion, and Wheaton Precious Metals Corp., $23.6 billion, account for 14.5 per cent of GDX’s holdings, and both are up, 15.7 per cent and 22.5 per cent respectively, since February 2020.

Exchange-traded funds backed by physical bullion offer yet another way for investors to gain exposure to gold without the environmental, social and corporate governance concerns that come with owning a mining company.

Advertisement This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

Perhaps the most visible alternative to gold or gold miners for investors looking for a hedge against fiat currencies, are cryptocurrencies such as bitcoin.

All of those factors have combined to foster a general feeling of pessimism in the mining sector, which was on display at the recent Association for Mineral Exploration Roundup 2022 conference in Vancouver in late January and early February.

There, Ian Telfer, a gold industry veteran who formerly chaired Goldcorp Inc. and currently chairs Aris Gold Corp., advised medium-sized companies to avoid “grassroots exploration,” because the chance of striking a motherlode is too small. Instead, he recommended growing by acquisition, even if it means overpaying for high-quality assets.

Advertisement This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

He also advised his audience not to put “wise and worldly” industry veterans on their boards of directors.

“The price of the commodity (gold) has outperformed all of the (gold mining company) shares, which is the opposite of what the industry tells the world,” Telfer said in an interview. “Because of the lack of returns, the financial markets don’t have time for it. There’s no compelling reason to own gold (mining) shares.”

Ian Telfer in 2015. Photo by Peter J. Thompson/National Post files He also reiterated his belief that the world has reached “peak gold,” meaning production will gradually level off, and that even ”a huge” spike in the price won’t have much effect.

But any malaise in the gold industry could also be the result of short-term memories. Gold’s ascent to US$1,862 per ounce today from US$300 per ounce two decades ago was historic, and perhaps anomalous.

Advertisement This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

There was probably more gold mined during that period than at any other time in history. The World Gold Council says it’s best estimate is that approximately 205,000 tonnes of gold have been dug up since the beginning of human existence. About 32 per cent, or 66,000 tonnes, was mined between 2000 and 2021, according to Metals Focus, a consultancy that studies gold supply.

Adam Webb, director of mine supply at Metals Focus Ltd., said advances in technology, such as new more efficient refining methods, as well as larger dump trucks have enabled miners to dig for gold on a vastly larger scale.

In the early 1900s, the world was producing about 300 tonnes of gold in an average year. Today, that number is closer to 3,500 tonnes.

Advertisement This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

“That gives you an idea of how things have ramped up over the last 100 years,” Webb said.

Finding gold is becoming more difficult, and grades of ore bodies are declining. Whereas in the past, gold miners may have looked for nuggets, today, gold is measured in grams per tonne of ore.

S&P Global Markets last July estimated that more than 329 deposits of gold were discovered between 1990 and 2020, but just 29 of them were found in the most recent decade.

Gold miners underground at a site in Ontario. Photo by Tyler Anderson/National Post “The severe lack of new major discoveries over the past decade is a result of companies focusing on advanced-stage assets and known deposits, rather than searching for new discoveries,” the S&P report noted.

Sean Boyd, chairman of Agnico, the largest gold producer in Canada and an ambassador of sorts for the industry with 37 years of experience, said the gold mining sector is in its best position in years, considering the overall debt level held by companies and the macro-economic environment.

Advertisement This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

Investors have been “indifferent,” but they could yet come around, he said in an interview. “I don’t know how many times I’ve sat there with the team and said, ‘We’re doing all the right things and nobody seems to care.’ It’s probably a dozen times. That’s why you keep your head down, doing smart things.”

Last week, Agnico completed its merger with Kirkland Lake Gold Ltd., one of a wave of combinations announced during the past few years as executives preach consolidation as a means to achieve larger, more efficient companies with more liquid stocks that would appeal to institutional investors.

More On This Topic Iamgold to shake up board as part of settlement with activist shareholder Gold miners Agnico Eagle, Kirkland Lake propose $13.5 billion mega-merger Barrick Gold lost its ‘social licence’ in Papua New Guinea. This is the price it’s paying to earn it back Mining’s biggest networking event of the year goes virtual after ’embarrassingly good year’ This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

Article content Privately, many gold mining executives lament that a new “boring” phase is starting. Miners will seek attention by announcing dividends rather than bonanza discoveries. Executives will seek growth through incremental expansion around existing mines and through acquisitions.

But believers such as Boyd aren’t ready to give up.

Sean Boyd, chairman of Agnico. Photo by Nick Kozak for Postmedia News files There’s at least one wild card that could shuffle the deck: inflation. The thing that spooked investors and spurred them to seek safety in gold stocks during the last recession is back, and this time it’s real. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics this week reported a 7.5 per cent annual gain in the consumer price index in January, the fastest year-over-year rise since 1982.

“How many times have I heard gold is dead, it’s a barbarous relic, the industry is finished,” Boyd said. “That’s why we’re making the case that there’s always room for a high-quality gold miner.”

• Email: gfriedman@postmedia.com | Twitter: GabeFriedz

Financial Post Top Stories Sign up to receive the daily top stories from the Financial Post, a division of Postmedia Network Inc.

By clicking on the sign up button you consent to receive the above newsletter from Postmedia Network Inc. You may unsubscribe any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link at the bottom of our emails. Postmedia Network Inc. | 365 Bloor Street East, Toronto, Ontario, M4W 3L4 | 416-383-2300