The Fed’s move to simultaneously hold interest rates and signal future rises may have been a strategy, David Rosenberg said. The central bank managed to find a way to “tighten policy without tightening policy,” the top economist tweeted. The Fed left rates unchanged this week, but indicated it may raise them twice more before year-end. Loading Something is loading.

Thanks for signing up!

Access your favorite topics in a personalized feed while you’re on the go.

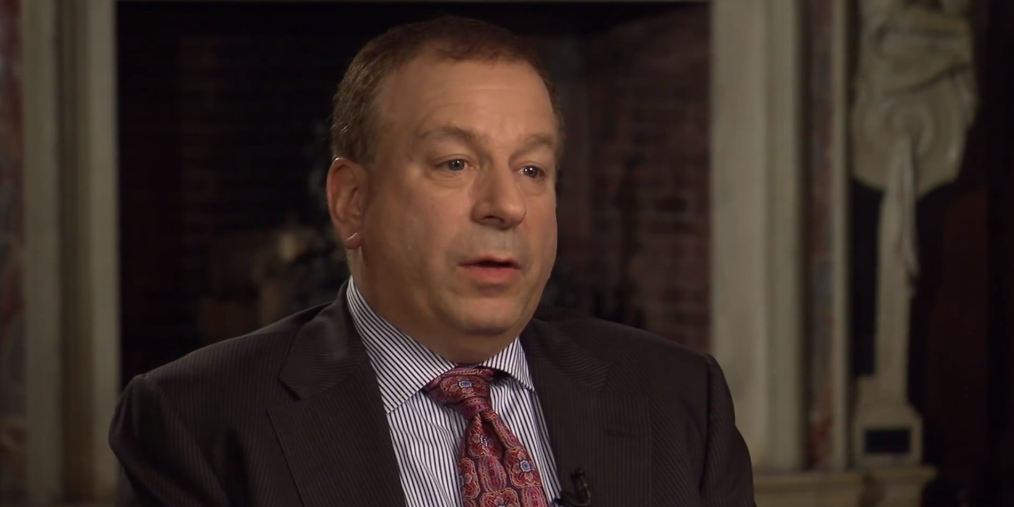

The Federal Reserve may have left interest rates unchanged this week – but by signaling future increases, it still effectively conveyed a tightening of policy, top economist David Rosenberg said.

“The Fed is a genius. It found a awy to tighten policy without tightening policy!,” the Rosenberg Research president and former chief North American economist at Merrill Lynch quipped in a tweet late Wednesday.

The US central bank kept rates steady on Wednesday, taking a break after 10 consecutive hikes over the past 15 months. But it also projected two more quarter-point increases before year-end.

That move – of simultaneously holding rates and signaling future rises – may have been a deliberate strategy on the Fed’s part in order to rein in financial-market speculation that the central bank’s policy tightening is nearing its end, according to Rosenberg.

“I’m thinking this move to signal two more hikes was a strategy to ensure that the stock market didn’t soar on the “pause” (okay, call it “skip”) as every Tom, Dick and Harry strategist was telling investors always happens when the Fed moves to the sidelines,” he tweeted following Fed Chairman Jerome Powell’s press briefing.

Rosenberg has made it clear over the past few months that he believes the Fed has done enough when it comes to raising rates. The central bank has raised rates from nearly zero to upwards of 5% since last spring in a bid to tame inflation, which is now cooling from the four-decade highs it hit in 2022.

Higher rates tend to slow the pace of price increases because they encourage saving over spending and make borrowing more expensive. But they also chip away at demand across broad strips of the economy, pulling down the prices of assets like stocks.