stocks

It’s been a volatile year for the market. One of the best ways for investors to smooth the ride is through a diverse selection of stocks and stock funds.With this year’s rough ride, you don’t need reminding that stocks are volatile. Their prices bounce up and down, sometimes in extreme ways. The U.S. market as a whole has produced average annual returns of about 10% over the past century, but it doesn’t go up 10% every year. In roughly one out of four years, it declines – sometimes a lot.

If stocks returned the same amount every year, then, like bonds, they would yield gains of only a few percentage points. High returns are the reward you get for enduring the fear (often the sheer terror) of watching pieces of your nest egg disappear into thin air.

People like me tell you to hold on. History shows that markets bounce back. But enduring sickening declines isn’t easy.

The best way to smooth the ride is through diversification. I’m not talking here about portfolio diversification – the allocation of your assets to stocks, bonds, cash and maybe more. Portfolio diversification is a necessity but a subject for another day. The topic today is diversification in the part of your portfolio that consists of stocks and stock funds.

The value of diversification seems awfully obvious. Morningstar data in June 2021 showed that about 39% of all U.S. stocks had ever suffered three-month losses of 50% or more, but fewer than 1% of diversified stock funds had incurred losses that severe.

Consider the sad tale of Enron, once a high-flying Houston energy company. When it collapsed in 2001, thousands of investors, including Enron employees whose retirement plans were heavily invested in the stock, suffered huge losses. Enron was the seventh-largest company in the Fortune 500, but in 2000 its market capitalization (price times shares outstanding) represented less than 1% of the value of the S&P 500 Index. If you had put $10,000 in an S&P 500 Index fund and all the other stocks maintained their prices, then Enron’s trip to zero would have cost you just $100.

Enron’s earnings per share had climbed from 9 cents in 1989 to $1.47 in 2000, rising in nearly every year. But the company was cooking its books. “Could the average investor have seen through [Enron’s] story and determined that the company was in trouble? Absolutely not,” I wrote 20 years ago. The smartest analysts missed it. The only protection was to diversify.

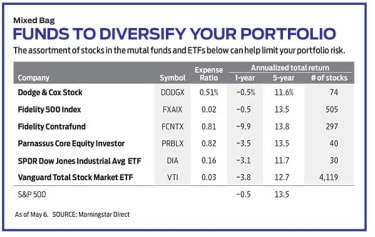

How Much Stock Diversification is Enough?How much diversification do you need? Certainly, owning an S&P 500 fund such as the Fidelity 500 Index (FXAIX), which holds about 500 different companies and is weighted by market capitalization, will do the trick. Or, for super-diversification, there’s the Vanguard Total Stock Market (VTI), an exchange-traded fund that owns 4,119 separate stocks. (Funds and stocks I like are in bold; prices and other data are as of May 6, unless noted otherwise.)

But what if you want to construct your own portfolio of individual stocks? A debate rages among economists over how many securities you need to get the benefits of diversification. More precisely, it’s a debate over how much adding extra stocks reduces your overall risk.

In a 1968 journal article, two University of Washington researchers, John Evans and Stephen Archer, said the minimum stock portfolio size should be 10. Another study conducted around the same time showed that standard deviation, a popular measure of volatility, was 49.2% with a portfolio of just one stock and 23.9% with 10. But after that, the study found, risk declines slowly – to 20.2% with a 50-stock portfolio, for example.

In 1987, finance professor Meir Statman disagreed. In a much-cited paper that used a different analytical method, he concluded that investors need “no less than 30 stocks.” Another group of economists, led by Harvard’s John Campbell, determined that you need 50.

In all these cases, however, the number of stocks is only part of a diversification strategy. You have to diversify by sector, too. If all 30 of your stocks were in energy, for example, your annual average return over the past 10 years would have been a miserable 5.6% (the performance of the S&P Energy Sector index), compared with an annualized 13.9% for the S&P 500 as a whole.

You also need to keep your portfolio as close to equally weighted as you can. You are not diversified if you own 30 stocks, with 29 of them each representing 1% of total assets and one of them representing 71%. The best way to stay balanced is to reallocate your holdings at the end of every year or six months. Sell shares of stocks that have grown sharply in value and use the proceeds to buy more shares of the laggards. Be aware that by selling profitable shares you will incur taxes, so try to use offsetting losses or restrict your reallocating to a tax-deferred account, such as an IRA.

The way I solve the portfolio-size conundrum is to own eight or nine individual stocks as well as diversified funds, such as the SPDR Dow Jones Industrial Average (DIA), an exchange-traded fund nicknamed Diamonds, which holds the 30 stocks in the Dow. The value of the assets in the stock and fund portions of my portfolio are roughly equal. If I owned only the stocks, I wouldn’t get enough diversification protection.

Do you need international stocks or small-company stocks as well as large-caps to get true diversification? I don’t think so. Certainly, invest in European mid-cap stocks, for example, if you think such a sector is undervalued, but if the objective is achieving market-level returns (or maybe a tad higher) while suppressing risk, the best strategy is to stick with U.S. large caps.

The Downside of Stock DiversificationBut diversification has costs as well. It dilutes strong convictions. Andrew Carnegie, who in his day was the richest man in the world, disdained diversification. He said in 1885, “The concerns which fail are those which have scattered their capital, which means that they have scattered their brains also. ‘Don’t put all your eggs in one basket’ is all wrong. I tell you, ‘Put all your eggs in one basket, and then watch that basket.'”

Warren Buffett, the CEO of the holding company Berkshire Hathaway (BRK.B), agrees. He says that diversification “makes little sense if you know what you’re doing.” The Berkshire Hathaway equity portfolio at the end of 2021 held 40 listed stocks, but 41% of those assets were in a single stock – Apple (AAPL) – and another 25% were represented by Bank of America (BAC), American Express (AXP) and Chevron (CVX). “I would say for anyone … who really knows the businesses they have gone into, six [stocks] is plenty,” Buffett says, adding that “very few people have gotten rich on their seventh-best idea.”

Most investors, however, don’t have the time or the inclination to “really know” those businesses. Instead, they are saving for a more comfortable life, retirement or security for their children, not to strike it rich. Such investors are happy – or should be happy – with an annual average return of 10%, which will quadruple their investment in about 15 years.

In addition to owning broad index funds, you can get strong diversification through low-cost managed funds. Dodge & Cox Stock (DODGX), for example, has an expense ratio of 0.51% and an annual average return of 14.0% over the past 10 years. DODGX – a member of the Kip 25, our favorite low-fee mutual funds – has a 74-stock portfolio, with the top 10 holdings representing only 32% of total assets, and a good mix by sector. Turnover is only 10% annually. The fund has held some stocks, including Wells Fargo (WFC) and FedEx (FDX), for more than 30 years.

Owning a single fund with a great track record like the Dodge & Cox fund – or Fidelity Contrafund (FCNTX), which has a much larger portfolio but is more top-heavy, or even the Parnassus Core Equity Investor (PRBLX) fund, with only 40 stocks but a broad combination of sectors – is really all you need to achieve solid diversification.

James K. Glassman chairs Glassman Advisory, A public-affairs consulting firm. He does not write about his clients. His most recent book is Safety Net: The Strategy for De-Risking Your Investments in a Time of Turbulence. He owns SPDR Dow Jones Industrial Avg. ETF. You can reach him at James_Glassman@kiplinger.com.