Value stock outperformance is in the early stages and has plenty of room to run

A specialist trader works on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange. Photo by Brendan McDermid/Reuters files Against a backdrop of sky-high inflation, rising rates and growing recession concerns, stocks have had a dismal year.

Advertisement 2 This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

Investors are now no doubt pondering the following three questions: How long will the carnage last? How much more will equities fall before hitting bottom? What might it take for equity fortunes to turn?

FP Investor By clicking on the sign up button you consent to receive the above newsletter from Postmedia Network Inc. You may unsubscribe any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link at the bottom of our emails. Postmedia Network Inc. | 365 Bloor Street East, Toronto, Ontario, M4W 3L4 | 416-383-2300

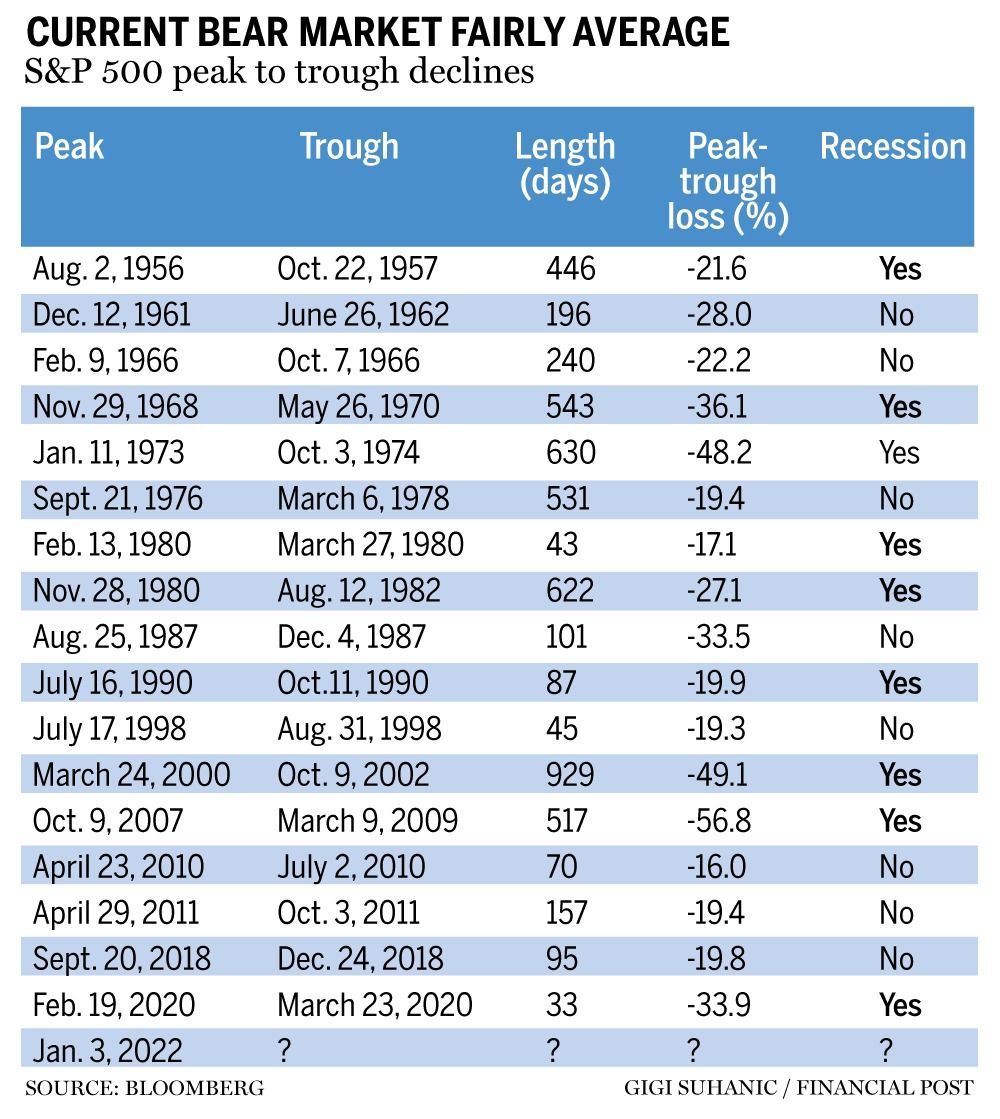

I analyzed all peak-trough declines of more than 15 per cent in the S&P 500 index since 1950 and found the average length of such declines was 310.9 days. Taking the recent peak on Jan. 3, 2022, the current bear market clocked in at 270 days as of the end of September. The time is near at hand when the current decline will have become average from a historical standpoint.

In terms of magnitude, the average decline was 28.7 per cent. As is the case with duration, we are nearing the point at which the current decline in prices can be construed as garden variety, with the S&P 500 index down 24.3 per cent through Sept. 30 from its early January peak.

Advertisement 3 This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

Of the 17 declines in the S&P 500 index since 1950, 14 have been at least five percentage points less or more severe than the average decline, and five of them have fallen outside of the +/-10 band of the average. This indicates there is no guarantee that markets will continue to decline until they match the historical average. Similarly, it is entirely possible the current decline will eventually exceed the historical norm, perhaps meaningfully so.

Past bear-market patterns can be well-summarized by the Latin expression “abyssus abyssum invocat,” which means “one hell summons another.”

Historically, once stocks have already suffered precipitous declines, they tend to continue falling over the short term. Of the eight losses that have breached the -25-per-cent threshold, the average peak-trough loss was 39.1 per cent. Put another way, during times when stocks declined by at least 25 per cent, the panic train went into high gear, with stocks declining a further 14.1 percentage points on average.

Advertisement 4 This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

Bear markets that have been accompanied by recessions have tended to be more vicious than their non-recession counterparts. Of the 17 declines in the S&P 500 index of at least 15 per cent, nine have been accompanied by recessions. The average length of these nine episodes is 427.8, a full 116 days longer than the average for all 17 observations.

Similarly, the average peak-to-trough decline in recessions was 34.4 per cent, a full 5.8 points worse than the full-sample average of 28.7 per cent, and 10.1 points more than the 24.3 per cent decline through the end of September from the Jan. 3 peak. If you think a recession is either highly probable or inevitable, you should not be in a hurry to add equity exposure.

It’s also worth noting that inflationary peaks by themselves have had a mixed record of predicting equity market bottoms. Some market troughs occurred at or near inflationary peaks, while others occurred well below this point. Inflationary peaks only coincided with equity market bottoms when they were accompanied by economic growth troughs.

Advertisement 5 This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

Peaks in inflation that proved to be a good time to own equities (December 1974, March 1980 and October 1990) occurred near economic troughs. In contrast, during two of the three times when it would have been a mistake to buy equities after inflation peaked (December 1969, January 2001 and July 2008), the economy was in or about to enter a recession.

Recommended from Editorial It’s time for investors to stop complaining and spending so much, save some money and put it to work Don’t let the market noise drown out what’s right for you Cash may be king, but cash flow rules in times of volatility The recent correction has clearly been driven by the United States Federal Reserve and other central banks raising rates at the fastest clip since the 1980s to bring inflation under control. Historically, this type of monetary policy-induced decline in stocks has ended once the Fed shifted towards easier policy.

This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

Article content In bear markets induced by monetary policy, the Fed has historically held the trump card. In such times, equities have almost always bottomed when the Fed began cutting rates, regardless of whether economic activity had troughed.

A clear signal that tightening risks are merely receding (rather than a wholesale shift toward easing) may be sufficient to stem and possibly reverse the downward trend in equities. This possibility likely depends on the state of growth and employment when central banks take their feet off the monetary brakes.

If neither the economy nor employment has materially declined, then a flattening out of rates is likely to coincide with a bottoming in equity markets. On the other hand, should the Fed wait for a more substantial deterioration before pausing, a trough in stock prices is more likely to require outright easing of monetary policy.

This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

Article content The TINA (there is no alternative) refrain was a common factor underlying the allure of equities after the global financial crisis of 2008, and perhaps even more so after the COVID-19 crash in March 2020. With bonds offering historically low yields, many investors felt they had little choice but to increase their allocations to stocks in order to achieve acceptable portfolio returns.

But the recent spike in rates has caused investor psychology to shift from TINA to TARA (there are reasonable alternatives), as the yields on cash and high-grade bonds have become increasingly attractive.

Relatedly, stocks are currently expensive relative to bonds. The accompanying graph illustrates that equity valuations have not come down meaningfully once interest rates are considered.

This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

Article content Despite the carnage in stocks, the gap between the forward earnings yield on equities and bond yields currently stands at one of the lowest levels since the financial crisis.

For stocks to become competitive with bonds from a valuation perspective, either stock prices need to fall further, earnings growth needs to accelerate, bond yields need to decline or some combination of the preceding three developments.

Importantly, if any of the first three variables moves in the opposite direction, this would require an even sharper adjustment in the other two factors to bring equity valuations in line with bonds.

I believe it would be prudent for investors who are reluctant to make changes to their overall allocations to stocks to shift from growth stocks into value-oriented companies with strong records of increasing dividends.

Growth stocks trounced their value counterparts in the post-financial crisis bull market. From the end of February 2009 through the end of 2021, the S&P 500 growth index outperformed its value counterpart by an astounding 424.2 per cent.

The recent outperformance of value vs. growth stocks has started to close the growth-value valuation gap, but it still remains near all-time highs. This suggests that value stock outperformance is in the early stages and has plenty of room to run.

Noah Solomon is chief investment officer at Outcome Metric Asset Management LP.